Networks are currently in the firing line for having spread coronavirus along with all the associated conspiracy theories that are only making matters worse. But networks are also critical to finding a vaccine and overcoming the dislocation of social distancing. A virile network will spread the good, the bad and the just plain ugly – it doesn’t care, but it would help if leaders and managers did.

The interconnectedness of the modern world has seen Covid-19 spread in just a few months from a human host somewhere in or around Wuhan, in the Chinese province of Hubei, to infect more than 700,000 people worldwide and cause 34,000 deaths so far. At the same time it has inspired countless wild stories about its origins, its effects and its cure: an escaped bioweapon, a disease treatable with oregano oil, or, incredibly, by gargling with bleach! On the positive side, interconnectedness may be its downfall, too. Scientists around the world are sharing knowledge and information to stop it.

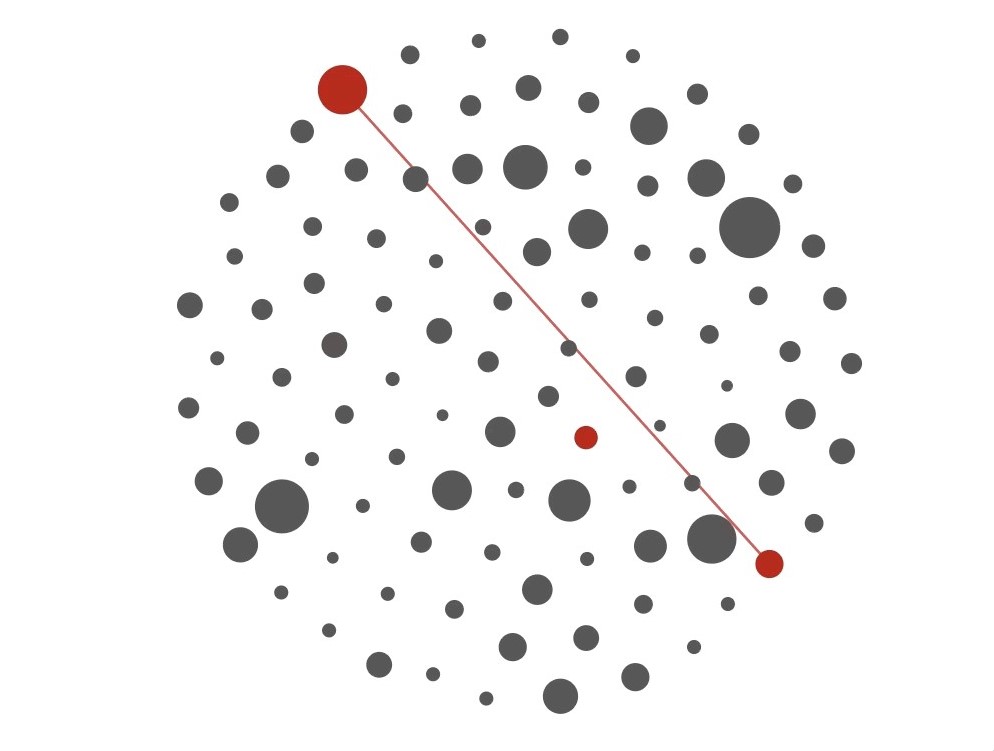

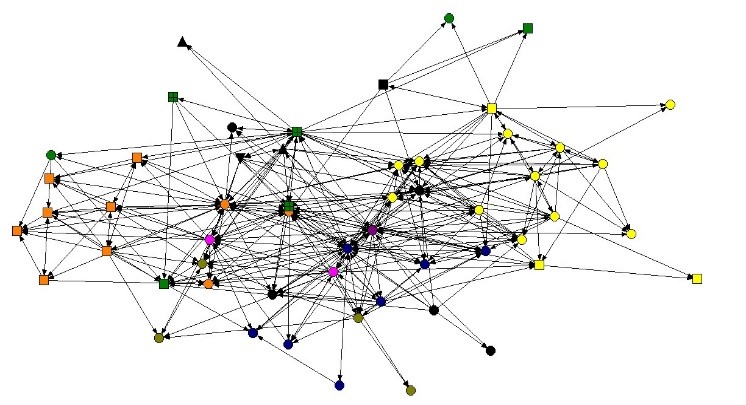

It will come as no surprise that there are two fundamental aspects to all human social networks: connection and contagion. Connection refers to the shape, structure, or anatomy of a network, the arrangement of its nodes (people or groups) and ties (connections between them). They are made visible using Network Visualisation Software, which creates a 2D picture of the network.

For example, the diagram below is a 2D visualisation which we created in order to analyse the connectivity in a multi-site public sector organisation. The coloured shapes are people (the colour denoting their team and the shape their location) and the arrow headed lines are the connections between them.

Contagion, on the other hand, refers to the networks function or physiology. What, if anything, flows through and across the connections, whether this be ideas, cute cat memes, behaviours, fake news or viruses. It is important to understand that the spread of an idea is just as much about the structure of the network as it is about the content of the idea. A virile network will spread an idea regardless of its veracity, hence fake news!

Contagion helps us understand how effects spread from person to person. It is also known as Hyperdyadic Spread, of which there are two varieties. The first includes germs, gossip and information, where once infected additional contact is redundant. The second are norms and behaviours, which often require reinforcement through multiple social contacts.

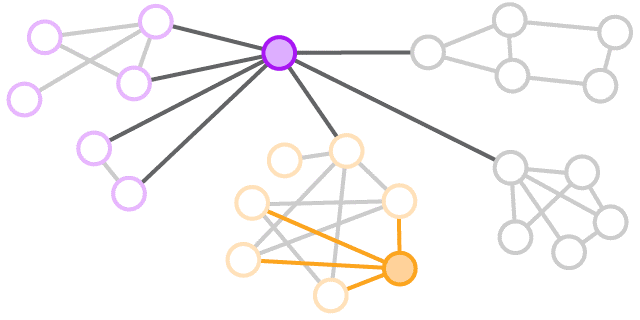

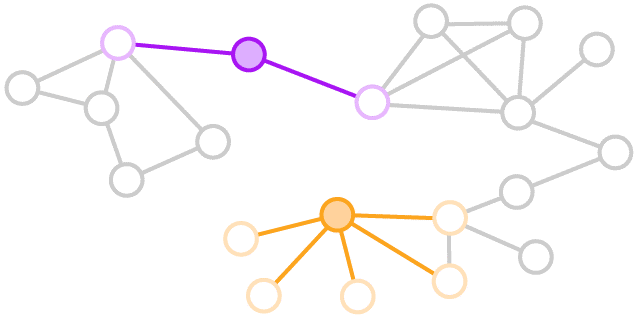

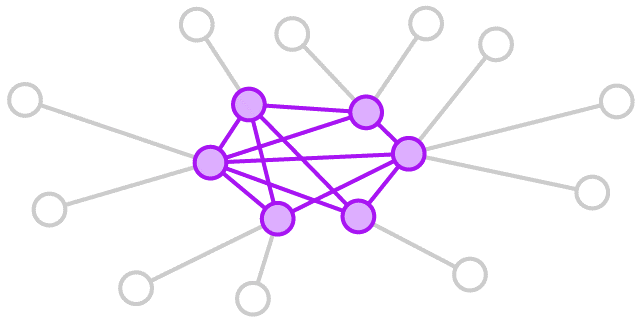

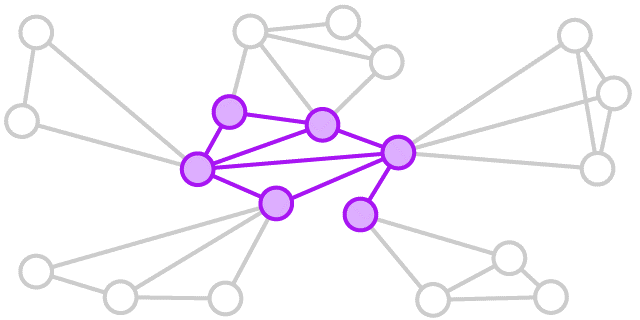

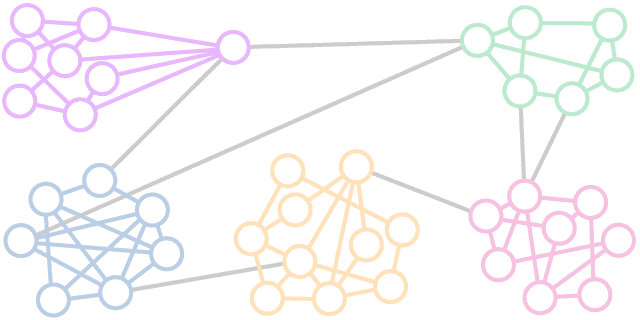

The following 2D visualisations, where the circles represent people, are provided to illustrate a few typical examples of contagion in a network, from ideas and influence to efficiency and effectiveness.

In the first example, purple is more likely to come up with good ideas. They communicate with people in several other networks besides their own, which makes them more likely to get novel information that will lead to good ideas. On the downside, this also means they are more open to germs and viruses. Orange, who communicates only with people within their network, is less likely to generate ideas, even though they may be creative, because the same ideas will tend to get regurgitated.

In the second example, although purple connects with only two people, they are still more influential than orange, because their connections are better connected themselves. Orange may spread ideas faster, but purple can spread ideas further, because their connections are more connected and therefore influential. Equally, however, purple is more likely to pick up passing germs and viruses.

In the third example, the purple team are likely to be high performing in the sense that they get things done quickly and efficiently, because the members of the team are deeply connected with one another. They have a high internal density of connections, which leads to shared understanding and trust. And because members’ external connections don’t overlap, the team also has access to a variety of helpful outside resources and ideas. On the downside germs or a virus will run riot.

In this example, the purple team members are not as deeply interconnected, they have lower internal density. However, this suggests a different strength, the fact that they don’t see eye to eye means they are more likely to have alternative perspectives, more-productive debates and consequently, if led and managed well, they will innovate more effectively. They also have diverse external connections, which will help them gain buy-in for their innovations. But again, a virus is likely to run riot around these interconnected groups.

In the final example, each colour represents a different team. People within the teams are deeply connected and are therefore likely to be efficient, but only one or two people in any team connect with people in other teams. In other words they are working in silos. This means that communication and the sharing of ideas is likely to be limited. So while they might be efficient (doing things right), they may be ineffective (doing the wrong things), because they have little idea how their piece of the organisation fits with the rest. So few connections between them also make the structure very fragile. The organisation is already siloed and it would get worse if key connecting individuals moved or left the business.

Collectively, the diagrams illustrate an important but neglected measure of an individual’s importance: their centrality to the network, the extent to which a person acts as a network bridge between different groups and actors. Crucial roles are played by people who are connectors and they are not necessarily leaders. Such individuals can be assessed in terms of their degree centrality, the number of people they are connected to; their betweenness centrality, the likelihood of them being a bridge between other nodes who would otherwise be disconnected; and their eigenvector centrality, their proximity to popular or prestigious nodes. The more central an individual the more likely they are to ‘catch’ what is passing through the network and pass it on.

With that in mind, I will leave you with some important network leadership questions to ponder…

- Do you know who the connectors are in your organisation?

- Is network connectivity in your organisation sufficient to enable efficient sharing of information, ideas and resources?

- Is the network expanding and growing more connected over time, or going into reverse?

- Does the network effectively bridge the gaps between teams and departments?

- Is the network structure appropriate for the work of the organisation?

- Are you making the most of your innovative capacity – both individuals and teams?

- And finally, how does all this play out in the current environment, when connectedness and the sharing of information, ideas and resources is more important than ever?